Trisha and Donna: Broadway's Finest

The grit and abandonment of two electric dancers' bodies in 1970s New York City.

In 2012, I traveled to Paris with my university, where we took classes at the Centre National de la Danse (CND) - a Brutalist-designed administrative center turned dance hub. Sitting in the center's chilly and uncomfortable lobby, I was watching videos being played from the center’s dance-on-film series. I became mesmerized when I saw, for the first time, the groundbreaking film of Trisha Brown’s seminal dance solo: Watermotor (1978).

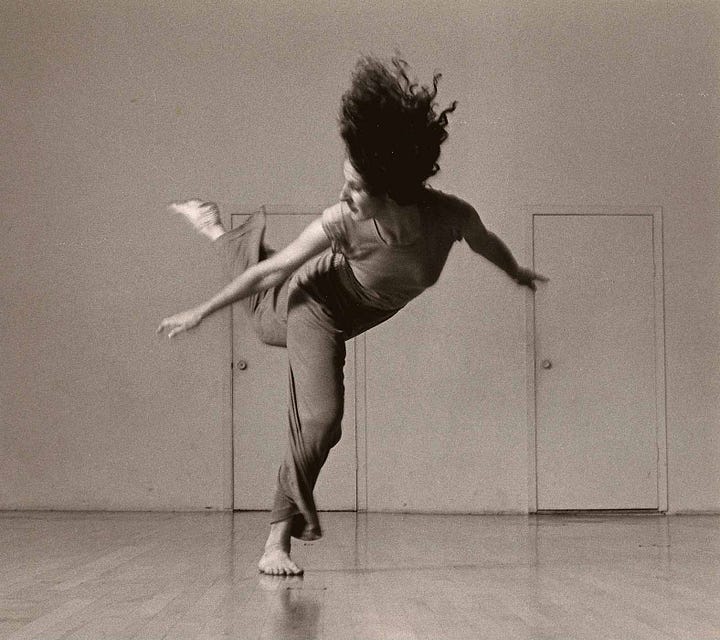

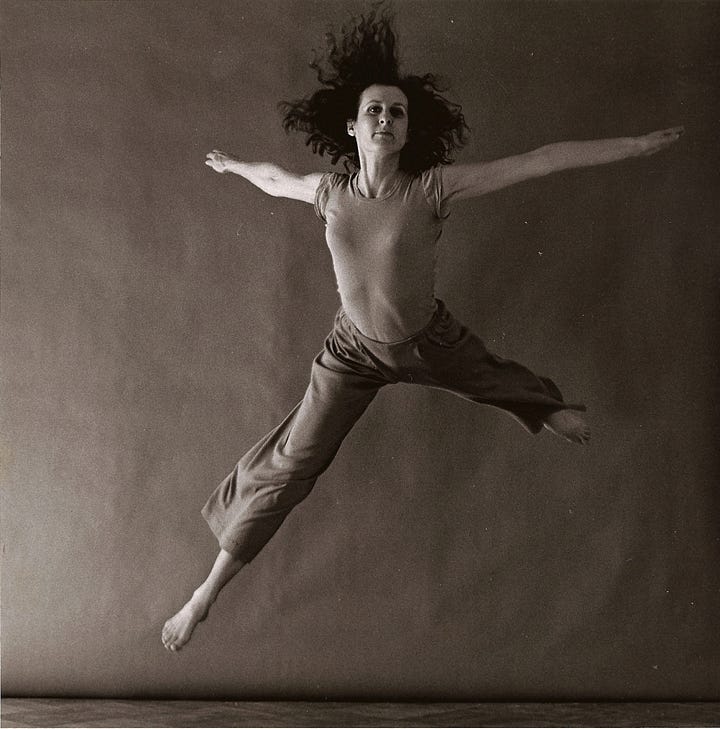

Directed by photographer and filmmaker Babette Mangolte, Trisha cut through space simultaneously with abandonment and specificity. Her groundedness was fleeting – a new idea would puncture her psyche and she would run (or hop, skip, leap, collapse, jump) to catch it. Watching her tear through space with such idiosyncratic ease, I experienced a profound awakening.

I had spent the previous couple of years discovering what my body was capable of by hurling my limbs through space, forsaking specificity in favor of abandonment. It felt better, or more honest, to literally throw my shapeless body around than to get caught in the intentional writing of movement. That feeling of freedom felt empowering but a certain intellectual rigor was missing to my approach and Trisha provided a thoughtful way in.

Watching her dance introduced another direction I could take as a dancer. She found a deep connection to the floor so that her movements, jagged and tossed, could communicate a precise yet almost childlike need to express. In her movement, she was revealing the possibilities one could encounter when conversing with their very own body - its weight and multitude of directions - and not an idea outside themselves.

A year later, I would be joining her company, performing her works on the roofs of the CND1 and eventually Watermotor.

When I joined the company, I learned everything I could about her, her dances and the dancers who interpreted her ideas. I tried my best to contextualize what she was making: she came to prominence in her 40s, in downtown New York City and made some of her most famous works at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Actively negating the need for storytelling or music in her work2, she was hell-bent on democratizing the whole body in pursuit of all of its possible arrangements. Her work came to be recognized for its emphasis on the body's geometry, as well as its exploration of opposing forces, gravity, inertia, and momentum.

Starting in 1979, Trisha began presenting complex and technically challenging group works that retained the same effortless and neutral qualities of her earlier explorations of everyday movement. However, prior to delving into these larger projects, she created Watermotor, an astonishing three-minutes of dancing that introduced a completely novel movement vocabulary, one that she and her peers had yet to encounter. It served as the foundational concept for her subsequent work: a lifelong exploration of the pedestrian body performing extraordinary feats.

Working primarily from her Soho loft on Broadway, between Prince and Spring Streets, I've often thought about the sharp disparity between Trisha's intimate dancing enclave and the mainstream grandeur of the uptown Broadway theater scene.

In 2020, I danced in the Broadway revival of West Side Story, choreographed by Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker and directed by Ivo van Hove. Working with Anne Teresa, a Belgian postmodern choreographer, I tried to inject my own and Trisha’s perspective on dance into a production of a scale this massive. It was an incredible challenge, seeing how the ideology of postmodern dance might or might not be able to tell a story the way a Broadway musical needs.

Broadway dancers, in the 1970s as now, are very different from “downtown” dancers. These worlds rarely collide. The dancers on Broadway are used as tools to propel a story forward as they provide immense entertainment with show-stopping numbers and tricks. Using the emotional arc of a show’s story and the music in order to build their movements was the very antithesis to what Trisha and her counterparts were exploring.

I tend to lean towards that mentality of Trisha and her cohort, believing that the body has so much to say without having to put on layers of emotional and musical weight. Even though I’ve spent years focused on embodying these ideologies, I do think that the world of dance on Broadway is quite spectacular. There are certain artists from that scene that I have been seriously affected by.

I specifically think of Broadway legend Donna McKechnie.

I first learned of her when I watched Every Little Step3, a documentary following the 2006 Broadway revival of the Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize winning musical A Chorus Line (1975). The documentary is incredible in telling the history of the making of the original show and displaying the high stakes and unbelievable talent of the dancers auditioning for the revival.

The show was created by Michael Bennett, a well-known choreographer on Broadway who shot to stardom with A Chorus Line. It is centered around a group of dancers auditioning for a show by baring their hearts to the show’s director, Zack, an ominous voice heard from the back of the house. Each of them tells their life story - inspired by the lives of the show’s actual dancers. The blurring of lines was revelatory and humanized dancers for one of the first times in theater.

The central and most tragic figure is Cassie, played by McKechnie, who has just returned to New York City, where she was always in demand, after a demeaning two years in Los Angeles auditioning for “dancing Band-Aid” commercials. Desperate for work, she pleads Zack for a job as a chorus dancer with an emotional and physical feat of a number, The Music and the Mirror4.

“God, I’m a dancer! A dancer dances.” - Cassie

It is a number to watch, but the Donna McKechnie video that has stuck with me is the 1969 Tony Awards performance of Turkey Lurkey Time from Promises, Promises - the Burt Bacharach and Hal David Broadway musical with choreography from Bennett.

The act one finale, Turkey Lurkey Time, was specifically designed to excite audience members and guarantee their return post-intermission, even though it had little to do with the actual plot of the show. It follows McKechnie as Miss Della Hoya and her fellow secretaries (Baayork Lee and Julane Stites) performing a dance number at the office’s holiday party.

When I first watched Donna take center stage in her red dress, I remember thinking she was one of the most technically skilled dancers I had ever seen. I was in awe of her complex movement pathways simulating that of a double-helix in motion. She imprinted curves and lines all around her as she carved what little space she actually had.

Sometimes on Broadway, dancers are subjected to cookie-cutter movements made under a time crunch from production. Donna and crew lucked out though with this choreography from Bennett. Donna, especially, makes the hilarity and wildness of these movements seem completely improvised. Her technique shines through amidst the mini explosions happening all over her body: the stretch in her arms, the heaviness and whip of her head. Her dancing, exacting and witty, asks me to commit more fully in my dancing by being more fearless and less serious. Donna’s rigorous joie de vivre serves as a reminder to me that there is always something higher to reach for and that talent is designed within.

Musical theater is a hard pill to swallow for some, and I understand why. It can feel self-congratulatory, corny, and out of touch with reality. I don’t disagree, but I think there are nuggets worth looking out for, especially during the boom of artistic innovation in 1970s New York. Exciting questions were being asked about the body’s capabilities and those answers were manifesting in hugely impactful ways.

Why are we mentioning Broadway legend Donna McKechnie in the same context as the mother of postmodern dance, Trisha Brown?

At the time Donna was premiering A Chorus Line at The Public Theater on Lafayette, Trisha was only a few blocks away still exploring what role her body and its pedestrian abilities played in the gallery and city spaces5. I have never heard of them crossing paths, but it’s fun to imagine Trisha making her way to The Public to see the show or Donna heading to a gallery performance of Trisha’s just around the corner. Their dancing signifies a very specific moment in time where it was imperative to have an exacting and impressive technique that allowed the political and social revolutions of the 60s and 70s to seep in, in unspoken yet affecting ways.

Donna’s dancing fills up time in such a way, similar to Trisha’s, that she must complete each idea right up until the point of crystallizing. Trisha would direct her dancers later on, saying “do it and get off it”. That’s what Donna and her do in their dancing. They execute movements to their fullest but move on with just as much assuredness - nothing is too precious. They let go but not without first making a point. Be there fully but don’t linger too long. The longer you remain, the less opportunity you’ll have to catch the wave of what’s to come.

These videos display amazing dancing, of course, but they specifically feel like dance to me because Trisha and Donna maintain an urgency that serves as a call to action. They ask me to seek excellence in many forms and to push myself to look out for ingenuity in my dancing and thinking. It is so easy to fall into the lineages we inherit, in dancing and in life, and take them as the standard to live up to. With dancers like them, I am forced to contend with the places I have yet to reveal to myself.

til next time,

marc

P.S. The closest crossover between Trisha Brown and the world of Broadway I’ve ever come across is this newspaper clipping from The New York Times with her and Broadway luminary, Stephen Sondheim side by side.

Myself performing in Roof Piece (1970) by Trisha Brown at Centre National de la Danse in 2015. www.numeridanse.tv

Trisha Brown on Pure Movement. Originally published in the Trisha Brown section of

Contemporary Dance, edited by Anne Livet, published by Abbeville Press, 1978. Reprinted in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961–2001, published by the Addison Gallery of American Art, distributed by MIT Press, 2002.

Trailer: www.youtube.com/everylittlestep

The Music and the Mirror, Donna McKechnie, A Chorus Line.